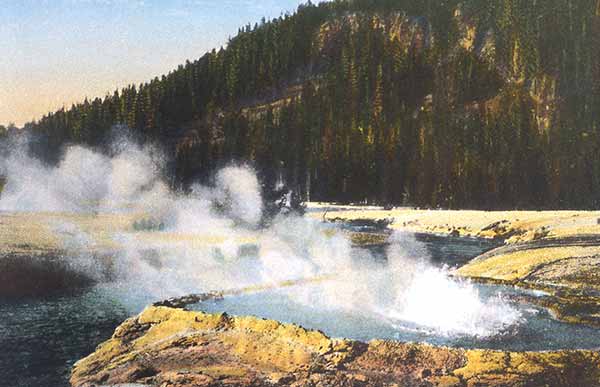

A postcard of Cliff Spring from 1928 based on a photo by Asahel Curtis. (NPS image)

By Mark Miller

By the early 1800s, trappers were scouring the Rocky Mountains for beaver. Evidence of their travel is sketchy, but we know that trapper brigades reached the Yellowstone plateau by 1826. An anonymous account of a trapper’s adventures in what is now Yellowstone National Park was published in The Philadelphia Gazette and Advertiser.

The identity of the author was revealed in 1947 when two elderly ladies offered to sell the National Park Service three letters that were in their family papers. A fur trapper named Daniel T. Potts had sent one of the letters to his brother on July 8, 1827. It is thought to be the first written description of the thermal features of the Upper Yellowstone by someone who actually saw them.

Potts wrote the letter at what is now Bear Lake, in Northern Utah. It was then called “Sweet Lake” to distinguish it from Great Salt Lake. Here’s Daniel T. Pott’s famous “Letter from Sweet Lake.”

Sweet Lake

July 8, 1827

Respected Brother,

Shortly after writing to you last year I took my departure for the Blackfoot Country. We took a northerly direction about 50 miles where we cross Snake River or the South fork of Columbia—which heads on the top of the great chain of Rocky Mountains that separate the water of the Atlantic from that of the Pacific. Near this place Yellowstone South fork of Missouri and the Henrys fork head at an angular point. The head of the Yellowstone has a large fresh water lake on the very top of the mountain—which is about 140 miles in diameter and as clear as crystal.

Mountain Man Sketch by E.S. Paxson, Montana Historical Society.

On the south borders of this lake is a number of hot and boiling springs—some of water and others of most beautiful fine clay. The springs throw particles to the immense height of from 20 to 30 feet in height. The clay is white and of a pink. The water appears fathomless; it appears to be entirely hollow underneath.

There is also a number of places where the pure sulphur is sent forth in abundance. One of our men visited one of those whilst taking his recreation. There at an instant the earth began a tremendous trembling. With difficulty he made his escape when an explosion took place resembling that of thunder. During our stay in that quarter, I heard it every day.

From this place by a circuitous rout to the northwest, we returned. Two others and myself pushed on in the advance for the purpose of accumulating a few more beaver. In the act of passing through a narrow confine in the mountain, we where met plumb in face by a large party of Blackfeet Indians. Not knowing our number, they fled into the mountain in confusion—and we to a small grove of willows. Here we made every preparation for battle. After finding our enemy as much alarmed as ourselves, we mounted our horses which where heavily loaded we took the back retreat.

The Indian raised a tremendous yell and showered down from the mountaintop. They had almost cut off our retreat when [we] put whip to our horses. They pursued us in close quarters until we reached the plains where we left them behind.

Tomorrow I depart for the west. We are all in good health and hope that this letter will find you in the same situation. I wish you to remember my best respects to all enquiring friends, particularly your wife.

Remain yours most affectionately.

—Daniel T. Potts

Read more tales of early travel in Yellowstone like this excerpt from Daniel T. Potts’ letter in Aubrey L. Haines’ The Yellowstone Story, in M. Mark Miller’s Adventures in Yellowstone: Early Travelers Tell Their Tales.

Written accounts from the early fur trappers in the Northern Rockies are exceedingly rare. A historian told me off the top of his head once that he figured there were maybe 350 unique mountain men in the employ of the bigger companies between 1820 and the mid-1840’s when the trapping era came to a close . There is no accurate census of the lone Free Trappers. He figured only a handful of any of them could even sign their own name or would be called ” literate”. Only a couple fur trappers kept any semblance of a journal or diary, the best being Osborne Russell’s daily journal from 1834 till 1943, which I consider gospel. The other trapper diary by Ferris is suspect, since it was written years later and contains known fallacies. Beyond those two journals everything else written by fur trappers was hit and miss in the form of sporadic correspondence or digested accounts extracted years later. A few of the early so-called expeditions had chroniclers. It should be noted that author Washington Irving accompanied the Bonneville expedition and wrote of the Astorians. But there isn’t a lot out there. Tall tales abound, however.

Thanks for your comment. You might be interested in the stories I’ve posted on my blog about early travel to Yellowstone Park (before the Model-T era). Here’s a link to get you started.

http://mmarkmiller.wordpress.com/2011/06/08/a-tale-osborne-russell-tangles-with-blackfeet-—-1839/