A bull elk pauses in the first light of dawn near Sylvan Lake in Yellowstone National Park.

The path to completion for many research and education proposals is often complex and baffling, and a new project to study and document elk migrations around Yellowstone National Park is no exception. It has connections with the most famous man in the world, touches on the inspirational story of a rotting whale and finds fruition through a century-old family legacy involving European royalty.

The project is being described by Yale University wildlife ecologist Arthur Middleton and South Dakota wildlife photographer Joe Riis as a rare and unique chance to discover and share details of a twice-yearly migration that is a defining characteristic of life in the greater Yellowstone area.

Wildlife ecologist Arthur Middleton speaks Thursday at a luncheon in Cody, Wyo. during which he was awarded the Camp Monaco Prize. Named after a 1913 hunting trip attended by Prince Albert I and William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody, the prize will fund research and education about biodiversity in the greater Yellowstone area.

The two men have been awarded the first Camp Monaco Prize, a newly established annual contest that will fund projects that combine research and public education about biodiversity in the region, and that also foster better understanding of related social and economic factors.

“This is an amazing opportunity for me,” Riis said Thursday at a luncheon in Cody, Wyo. announcing the $100,000 prize funded by the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Draper Museum of Natural History, the University of Wyoming’s Biodiversity Institute and the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation-USA.

“There is no publication or person in the world that would give me this kind of opportunity to photograph a single subject over two years,” said Riis, an Emmy award-winning photojournalist and cinematographer and National Geographic Young Explorer.

The prize offers a chance to learn more about what Middleton called a “defining ecological feature” of the greater Yellowstone area, and one that “binds the landscapes together.”

Middleton recently published the findings of earlier research that suggests drought plays a greater role than gray wolf predation on reduced reproduction rates in the Clarks Fork elk herd, near Cody.

Their Camp Monaco project will span two years of research and documentation on the migration of elk from the South Fork of the Shoshone River near Cody through the remote Thorofare region at the southeastern boundary of Yellowstone Park.

Most famous man

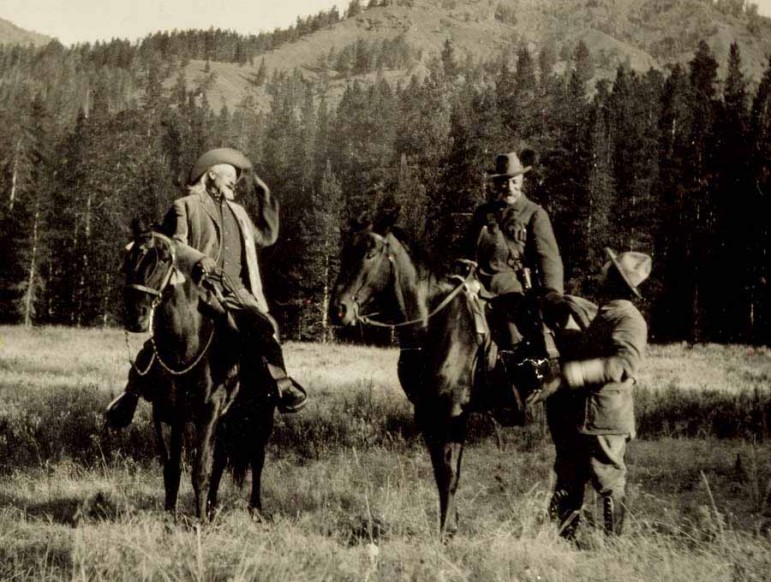

The Camp Monaco prize is named for a hunting camp established just east of Yellowstone in 1913 by Prince Albert I of Monaco and William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody. Albert I was the first sitting European head of state to visit the U.S., and sought out Buffalo Bill, who was then arguably the most famous man in the world.

William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody (left) looks on as a man speaks with Prince Albert I of Monaco (on horseback) during the prince's 1913 hunting trip to Wyoming.

On hand for Thursday’s luncheon in Cody was Prince Albert II, the current head of state for Monaco, a tiny city-state on the Mediterranean Sea near the French-Italian border that is famous as a playground for the rich and famous who are drawn to its gambling, nightlife and luxurious coast.

Like his great, great-grandfather, Prince Albert II has an interest in the natural world, and his foundation has funded more than 200 projects aimed at environmental research and conservation.

Prince Albert II said his namesake had always sought to link art and science, and would have seen the Camp Monaco prize as a fitting legacy of the hunting trip with Buffalo Bill.

It was the senior prince’s interest in forestry and marine science, among other things, that struck a chord at an early age with Carlos Martinez del Rio, director of the UW Biodiversity Institute and a juror for the Camp Monaco Prize.

A hand-colored photograph from 1897 shows Prince Albert I of Monaco observing a shipboard necropsy of a juvenile sperm whale.

Martinez del Rio recalled reading a historical account that described Albert I “diving into a rotten whale” during a necropsy aimed at learning more about marine biology. Martinez del Rio said it was one of the things that inspired him to become a biologist.

Today, Prince Albert II continues to focus on marine life, with a special interest in dolphins and ocean acidification driven by rising temperatures.

The prince said Thursday that “climate change is absolutely real, it is happening,” and that researchers “have to try to find ways to mitigate that.”

Prince Albert I of Monaco tries on a Stetson hat given to him Thursday during a luncheon in Cody, Wyo. to celebrate the launch of the Camp Monaco Prize. Named after a 1913 hunting trip attended by Prince Albert I and William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody, the prize will fund research and education about biodiversity in the greater Yellowstone area.

That blunt assessment of climate change might not find a welcome audience Saturday, when the prince will be the honored guest at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Patrons Ball. Thanks in part to the buzz around the prince’s attendance, the center’s largest annual fundraiser is sold out for the first time in its 37-year history, said Center development officer Gina Schneider. The royal visit also has attracted record contributions from donors, including lead sponsors Chevron and Marathon Oil.

Perhaps just as unpopular as a discussion topic among the ball’s well-heeled attendees might be Monaco’s longstanding reputation as a haven for members of the global wealthy elite seeking to dodge taxes. The principality faced widespread criticism after being blacklisted as a tax haven in 2004 by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. It has since taken some steps toward greater banking transparency and cooperation with international criminal investigators, and was removed from the OECD list in 2009. But critics say additional reforms are necessary.

Pivotal landowners

The high-profile royal visit has helped focus media attention on elk migration and biodiversity conservation, said Doug McWhirter, a Wyoming Game and Fish biologist who has collaborated with Middleton on elk research.

McWhirter said it was “pretty cool” to see so much fuss over wildlife research, and that the message was reaching the right crowd. Scattered among the more than 170 attendees at Thursday’s luncheon, McWhirter noted, were the owners of many of the largest private ranches that include tracts of key wildlife habitat between Cody and Yellowstone.

“These landowners are pivotal to what happens with all of this,” he said.

Sharing the story of elk migration around Yellowstone has implications across vast stretches of lands managed by many different state and federal agencies, said Draper curator Charles Preston.

While much of the habitat and wildlife populations in the greater Yellowstone region are in better shape now than a century ago, when Camp Monaco was established, Preston said, the winning proposal “makes us ever-mindful of the chaos that is trans-boundary stewardship.”

Liz Storer, president of the George B. Storer Foundation in Jackson, Wyo., said she was impressed with Riis’ acclaimed work documenting pronghorn migration, and lent early support for his elk migration proposal.

“This project encompasses good scientific work and also great storytelling,” she said.

Middleton hopes the project will remind area residents who might take elk for granted how compelling their spring and fall migrations are.

“It’s a chance to help them realize or rediscover the spectacle that’s taking place right in their own backyard,” he said.

Riis said he looks forward to the challenge of relying on perhaps only 15 or 20 still images and a 15- or 20-minute film in telling the story of spring and fall elk migrations and their connections to surrounding people, landscapes and other wildlife.

Though he will work on the project for two years, Riis said he knows he will have only four chances to capture the migration.

“I’ve got one fall and one spring to figure it out, and then one fall and one spring to get at the soul of the story,” he said, pausing to reconsider the challenge. “But if it takes longer, I’ll stay.”

Contact Ruffin Prevost at 307-213-9818 or ruffin@yellowstonegate.com.