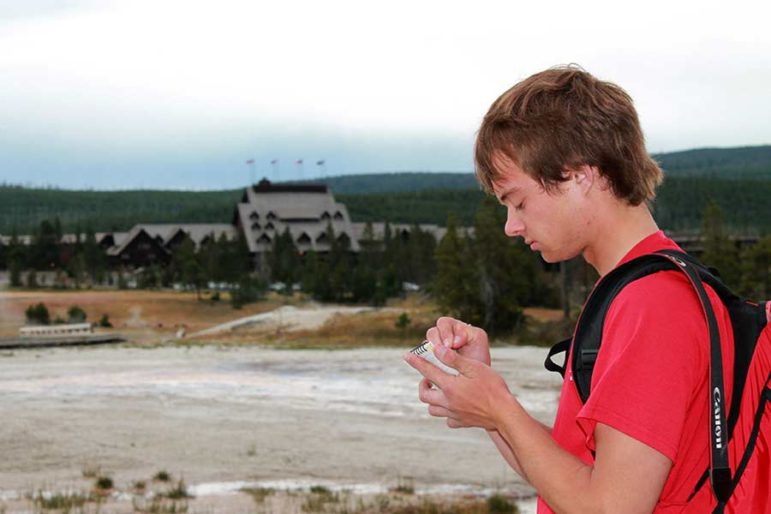

Self-described "geyser gazer" Ryan Maurer takes notes after the eruptions of Lion Geyser in Yellowstone National Park.

If we hear Fan and Mortar might go, we’re going, Ryan Maurer told me. It was about a mile-and-a-half run from the boardwalk where we stood near Old Faithful in Yellowstone National Park to the geysers near Morning Glory Pool. We’d have about 20 minutes of lead time from when it starts to the main blast.

Maurer, of course, has seen the concurrent eruption of Fan and Mortar with about a dozen vents streaming water that jets like a released fire hose more than 100-feet in the air.

But it’s a rare eruption to catch. It was active this summer, meaning eruptions came every three to 10 days compared to periods of inactivity where it can be weeks between shows. Maurer once sat 12 hours in front of it, watching and waiting.

People cheer and sometimes cry when it goes, he said. And by people, he means people like him—geyser gazers.

Yellowstone is home to two-thirds of the world’s geysers, attracting visitors from around the world. Most catch Old Faithful and may wander the boardwalks and accidentally witness other eruptions.

Some look at the schedule in the visitor’s office listing the times for the six predictable regular geysers, Great Fountain, Grand, Castle, Daisy and Riverside along with Old Faithful, and plan their day in hopes of catching those in action. But a dedicated few devote weeks, and sometimes entire summers, to waiting, watching and recording eruptions. These are geyser gazers and members of the Geyser Observation and Study Association.

Lion Geyser erupts in Yellowstone National Park.

The association formed in the early 1980s as a way to collect and share information on Yellowstone’s eruptions, said David Monteith, president of the organization and a member since 1993. It’s hard to pin down how many people are members, but on an afternoon in July, at Grand Geyser, there can be 50 geyser gazers watching along with 300 other park tourists, Monteith said.

Group members communicate via the same radio channels and document observations the same way – military time to the minute. That and following park rules is all that membership entails. Not every geyser gazer in the mark is a member, but most of the serious ones are, Monteith said.

It’s easy to spot a geyser gazer, Will Boekel said while working his shift at the Old Faithful Lodge, a job he took while on summer vacation from Montana State University so he could watch the geysers on his days off. Look for floppy hats, radios and people writing in their notebooks. Oh, and the cheering.

Watching a geyser with a serious geyser gazer is like watching a sporting event.

“Come on,” one chanted. “Go. Go.”

Chants are followed by whoops similar to the sounds a fan makes when a favorite team scores a touchdown, or the sharp mutters of disappointment as though you personally could have done better.

Maurer, 19, first visited Yellowstone National Park in 2001. Beehive with its jet engine roar and stream of water reaching 200 feet hooked him.

He knows the eruption schedules of every geyser in the basin. Each geyser has a personality and its own ticks, like a pool draining or filling, which hints at when it might go.

It takes patience and sometimes hours of sitting to catch some.

“The best way to see a geyser erupt is to see it not erupt for a very long time,” he said.

The organization isn’t formally affiliated with Yellowstone National Park, although many members volunteer with the park and roam the geyser basin talking to visitors about the thermal features, said Rich Jehle, the south district resource education ranger in the park.

They also report eruptions and observations to the visitor’s center via radio. A few veteran gazers are even allowed to record in the official park logbook. The data better helps the park predict the eruption windows for visitors.

Predicting eruptions is an art as much as it is a science, Jehle said. The geyser gazers keep copious notes and log hours of observations — even when they aren’t in the park. The visitor’s center will sometimes get a phone call reporting an eruption from a gazer who is at home watching a web cam.

Maurer doubts he’ll return to Yellowstone next summer. He’s studying aerospace engineering and will likely need to get “a real job.”

But he’ll continue watching the geysers from afar via web cams.

Last winter he called fellow gazer Mara Reed who answered the phone only to hear Maurer shout “Giantess,” repeatedly. She got online and together, she in Minnesota, he in West Virginia, they watched the geyser which only erupts a few times a year spray water 200-feet in the air.

Reprinted with permission from “Peaks to Plains” a WyoFile blog focusing on Wyoming’s outdoors and communities. Kelsey Dayton is a freelancer and the editor of Outdoors Unlimited, the magazine of the Outdoor Writers Association of America. She has worked as a reporter for the Gillette News-Record, Jackson Hole News&Guide and the Casper Star Tribune. Contact Kelsey at kelsey.dayton@gmail.com and follow her on Twitter: @Kelsey_Dayton.