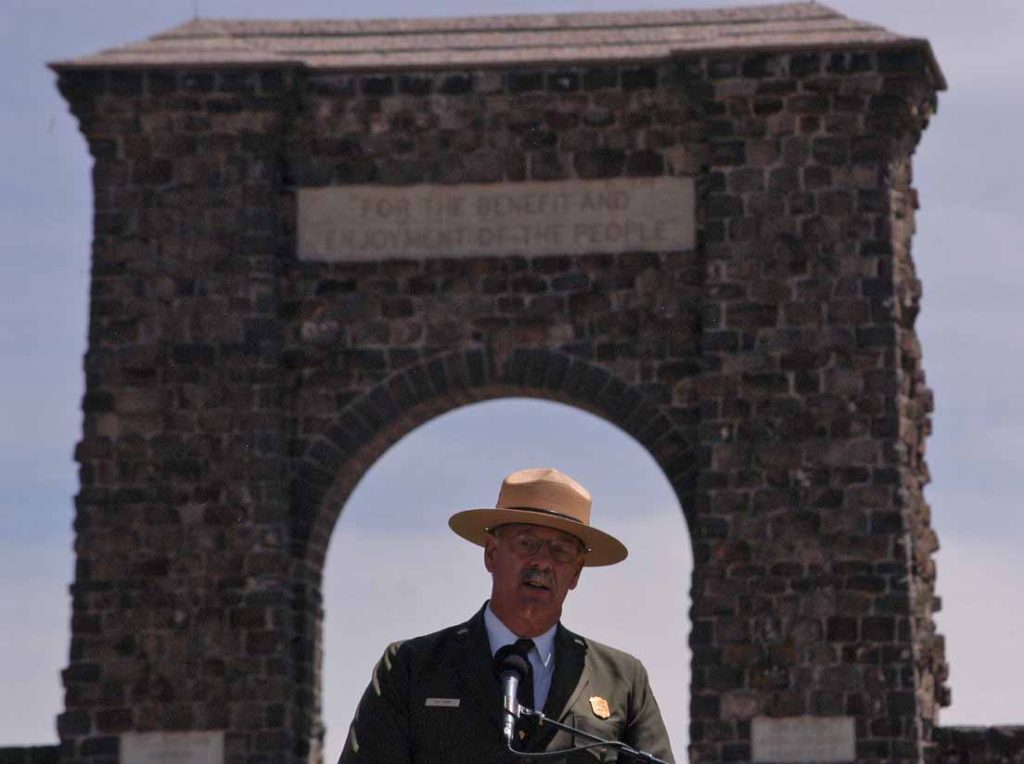

Yellowstone National Park Superintendent Dan Wenk speaks this summer in front of the Roosevelt Arch during a kickoff event for a project that will reconfigure the North Entrance to the park. (Ruffin Prevost/Yellowstone Gate - click to enlarge)

By Ruffin Prevost

CODY, WYO. — As another winter season in Yellowstone National Park begins, it might be understandable if some local residents are pessimistic about resolving long-standing disputes over snowmobiles in the park and other related winter-use issues.

Local tourism workers and environmental advocates have had front-row seats to more than a decade of public debate and court challenges over the effects of snowmobiles in the park, as well as whether to maintain access over Sylvan Pass, at the park’s East Entrance.

So it is perhaps surprising that gateway community business leaders are expressing optimism—even satisfaction—with the direction park managers are taking on winter use. And not just because the most recent draft plan calls for continued snowmobile access and keeping Sylvan Pass open.

They credit outreach from park staff members, especially Superintendent Dan Wenk, with creating a sense of inclusion and cooperation in the process.

Those who know Wenk and who have worked closely with him say his straight-ahead and direct style is well-suited to tackling thorny issues, and that he is committed to reaching a winter-use solution that will stand up to court challenges, protect the park’s resources and allow gateway communities to continue to contribute to winter visitation in Yellowstone.

“He’s just unflappable,” said Alma Ripps, deputy chief of staff for National Park Service Director Jonathan Jarvis. “I’ve never seen him lose his temper, ever.”

Ripps works in the Washington, D.C. headquarters of the National Park Service, and has known Wenk for 12 years. For the last year before Wenk was transferred to Yellowstone, Ripps worked closely with him on a variety of issues.

She described Wenk as “a calm island in a sea of frenzy,” and someone who is passionate about defending the Park Service and its mission.

When Wenk was the deputy director of operations for the Park Service—the highest non-appointed position at the agency—his work included standing up to tough and sometimes hostile questions while testifying before Congress, Ripps said.

Ripps said she wasn’t surprised to learn that Wenk, who started with the Park Service in 1975 and worked as a landscape architect in Yellowstone from 1979-84, was leaving Washington to become Yellowstone’s superintendent.

“His heart is in the parks,” she said. “That’s where he’s most happy.”

Wade Vagias, Wenk’s management assistant who has been tasked with crafting a winter-use plan that will meet agency goals and withstand legal challenges, had an offer to be the superintendent of a Park Service unit in Wisconsin. But at Wenk’s request, Vagias stayed on at Yellowstone.

Though that decision was based on a number of factors, including a desire to keep his family in Yellowstone, Vagias said he was also motivated to stay so that he could help wrap up the winter-use plan and learn from Wenk.

“I have the utmost respect for Dan,” Vagias said. “I’ve had the benefit of good mentors, and he’s top amongst those.”

Vagias said Wenk started his tenure at Yellowstone in February 2011 with no preconceived notions, knowing that the most important issues would quickly become self-evident.

Vagias described Wenk as “incredibly proactive” in seeking out public opinion, and said the superintendent was “acutely interested in learning the players and positions and understanding the values that underpin winter use.”

A collared elk is wary, but appears relatively undisturbed by passing snowmobiles in Yellowstone National Park. (Ruffin Prevost/Yellowstone Gate file photo - click to enlarge)

Gateway praise

In tourism-dependent gateway communities like West Yellowstone, Mont. and Cody, Wyo., Wenk has won praise from key players in tourism and snowmobile circles.

“He seems to be trying to work with everybody,” said Bert Miller, vice president of the Wyoming State Snowmobile Association. “We’ve had some very good dialog.”

Snowmobiling throughout Wyoming generates $147 million in direct annual spending and supports the equivalent 1,300 jobs, according to a report released this month from the University of Wyoming. The activity generates $7.4 million in annual state and local government revenue.

Yellowstone, while not the main driver of those numbers, is seen by many sledders as a place where snowmobiling should be defended at all costs as a stand on principle.

In West Yellowstone, snowmobiling in and around the park is a major part of the local winter economy.

“Working through winter access, there have been multiple times that Dan came and also brought his staff for updates,” said Jan Stoddard, marketing director for the West Yellowstone Chamber of Commerce.

Stoddard said she has heard mostly positive comments about how winter-use planning has progressed since Wenk arrived, and that the lines of communication extend to other issues as well.

“There’s been more of a proactive communication on everything,” she said. “There’s now a constant stream of education and information coming that that really helps us with visitors.”

Scott Balyo, executive director of the Cody Country Chamber of Commerce, said Wenk has met with business owners and others in informal gatherings separate from the public meetings that can often become supercharged with emotional rhetoric from partisans on all sides.

Perhaps the most contentious such meeting on winter use came in March 2007, when then-Superintendent Suzanne Lewis faced a rancorous crowd of more than 500, most of whom were upset with a proposal to close Sylvan Pass. Lewis cited avalanche risks along the pass as the key factor in her decision. The closure would have cut off winter access from Cody, except for those willing to snowshoe or ski more than nine miles from outside the East Entrance over the 8,524-foot pass.

Lewis was accompanied at that forum by several armed law enforcement officers, a move explained by park staffers at the time as standard procedure for public meetings. But no similar police presence has been seen at any Cody event since then.

Though the preferred alternative from Lewis called for closing Sylvan Pass, public outcry from Cody residents and pressure from Wyoming elected officials brought about a working group and discussions with park officials that later resulted in a reversal of that decision.

Wenk has faced criticism from several conservation groups objecting to the risk, cost and environmental effects of using a howitzer cannon to mitigate avalanche risks along the pass, which sees only a tiny fraction of the traffic found along other winter routes in the park.

“I think it’s important to acknowledge that Sylvan Pass is probably one of the most controversial aspects of this plan,” Wenk told Yellowstone Gate during a July interview before a public winter-use meeting in Cody.

Wenk said he doesn’t have a figure in mind for how many daily visitors might justify the cost or risk of maintaining the pass.

Sylvan Pass has been managed safely under a plan developed through Lewis and the local working group, and staff analysis has shown that access over that route is appropriate, he said, so it remains open under the latest draft of the plan.

Yellowstone National Park road crews and avalanche experts work to clear Sylvan Pass of more than 20 feet of snow from a May 2011 slide that injured no one but partially buried a Park Service vehicle. The slide temporarily closed the pass to vehicle traffic. (NPS photo)

‘Transportation events’

Wenk takes a similarly agnostic approach to snowmobiles in the park, saying the preferred alternative in the plan assumes that it is appropriate for over-snow vehicle travel in the park.

“So if the basic premise is that access is appropriate, and if the impacts between snowmobiles and snow coaches are comparable, it shouldn’t matter what provides that transportation in the park,” Wenk said.

Which is why the plan measures winter travel impacts according to “transportation events,” a move that aims to defuse the controversy over specific numbers of machines in the park, and even whether snowmobiles are appropriate. Instead, vehicle travel of any kind is evaluated based on sound, emissions and effects on wildlife.

The concept is the first major new approach to the winter-use deadlock in a decade, and could provide a path forward for eventually judging snowmobiles and snow coaches by a common, or at least comparable, standard.

Provisions in the plan for keeping Sylvan Pass open and maintaining, or even raising, total numbers of snowmobiles on peak days have not been popular with conservation groups. But some of those environmental advocates who object to aspects of the plan still praise Wenk’s outreach efforts.

“I think he’s doing a phenomenal job,” said Barb Cozzens, northwest Wyoming director for the Greater Yellowstone Coalition.

Though GYC has called for closing Sylvan Pass in the winter and phasing out snowmobiles entirely, Cozzens said Wenk “is the embodiment of what we look for in community-based conservation.”

Cozzens praised Wenk for his willingness to collaborate with other groups and agencies and to engage the public on difficult issues.

Both Vagias and Ripps said Wenk works hard to listen to stakeholders, but isn’t shy about making difficult or unpopular decisions and defending those decisions when challenged.

Such a defense may become necessary early next year, when the Park Service is expected to issue a final supplemental Environmental Impact Statement and a proposed rule to guide long-term winter use.

If the past decade is any guide, one or more parties unhappy with that proposed rule will challenge it in court.

Wenk said that he has looked at the last six failed winter-use plans to make sure all issues brought up by federal judges are addressed.

“But you can never arm yourself against someone taking you to court,” he said. “I’m not driven by that. I’m driven by doing the best plan we can do.”

Vagias said Wenk has always maintained that “any action is defensible as long as it is consistent with applicable laws, regulations and policies of the Park Service. In all instances, I see him apply that filter to his decision making.”

Wenk dealt with “the biggest, ugliest, hairiest issues” while director of operations for nearly 400 Park Service units from 2007-11, Vagias said.

But winter use is hardly the only contentious issue in Yellowstone. Some Cody business owners have grumbled about slow repairs to a damaged section of road between the East Entrance and Fishing Bridge. Many landowners and public officials around Gardiner, Mont. are unhappy with Park Service efforts to find more room for bison to roam outside the park during harsh winters. And wolves and grizzly bears continue to be an evergreen source of disagreement.

“I would say that I have not yet found an issue in Yellowstone that’s not controversial,” Wenk said. “But I really can’t imagine if people didn’t care passionately about Yellowstone National Park. And I’m glad they do.”

Contact Ruffin Prevost at 307-213-9818 or ruffin@yellowstonegate.com.